Getting It Right and Getting It Wrong on the “Real Costs” of Higher Education

This from the

Academe Blog (April 6):

In the Sunday Review section of the New York Times, Paul F. Campos has offered his opinion on “The Real Reason College Tuition Costs So Much.” [The whole piece is available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/05/opinion/sunday/the-real-reason-college-tuition-costs-so-much.html?smid=fb-share&_r=0]

Campos argues that attributing the rise in tuition costs to

reductions in state funding is a fairy tale that administrators have

been telling to cover up the tremendous increases in administrative

positions, administrative compensation, and administrative support staff

that have been the major drivers of increased costs.

He has gotten it half-wrong and half-right–if one is feeling very generous toward him..

Campos asserts: “In fact, public investment in higher education in

America is vastly larger today, in inflation-adjusted dollars, than it

was during the supposed golden age of public funding in the 1960s. Such

spending has increased at a much faster rate than government spending in

general. For example, the military’s budget is about 1.8 times higher

today than it was in 1960, while legislative appropriations to higher

education are more than 10 times higher.”

He provides no sources for these numbers, but using 1960 as a

baseline is very problematic for several reasons: (1) none of the baby

boomers had yet entered college; (2) to accommodate the baby boomers in

the 1960s and 1970s, every institution is the country dramatically

increased the size of its facilities and its faculty, many new

institutions were established, and the public community college system

was dramatically expanded; (3) to keep college affordable, very

inclusive federal grant programs, such as the Basic Educational

Opportunity Grants (BEOG), were established. All of these things

dramatically increased the expenditures on higher education. If the G.I.

Bill opened college to many veterans, the expectation in the 1960s had

become that anyone who wanted to attend college would be able to afford

to do so. In a very real sense, using 1960 as a baseline for tracking

increases in spending on higher education is comparable to using 1935 as

a baseline for tracking increases in defense spending.

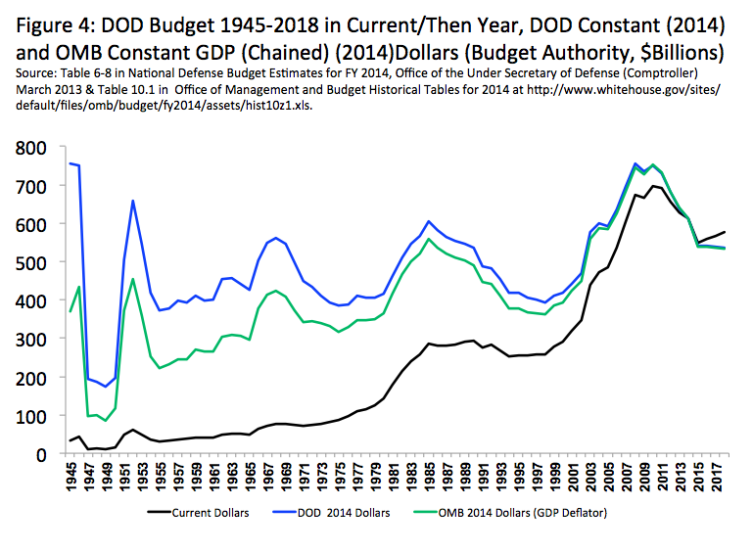

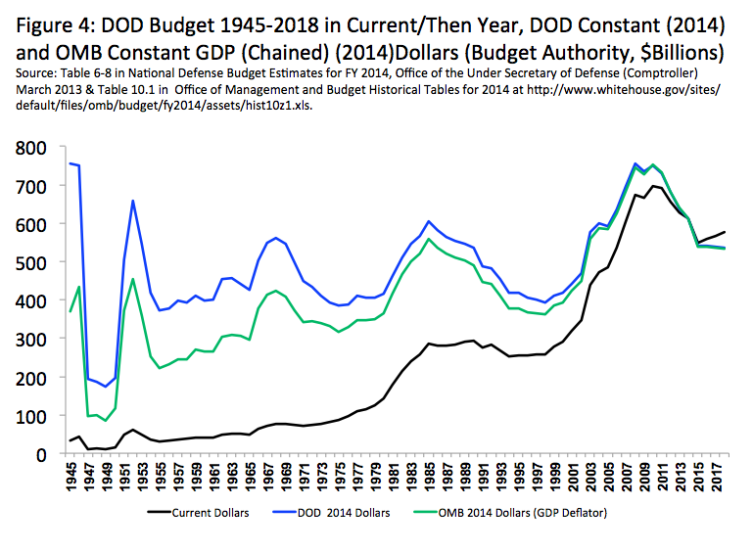

Moreover, Campos’ assertion that defense spending is 1.8 times higher now than in 1960 is very dubious. In July 2013, Time

magazine ran a series on the real cost of Defense, and the second

article in that series explored how the calculations that the Department

of Defense commonly uses to understate the increases in Defense

spending are markedly different from the calculations used to track

every other area of government spending and every other type of economic

activity. The full article is available at: http://nation.time.com/2013/07/16/correcting-the-pentagons-distorted-budget-history/ It includes this chart, with the black line showing the increase since 1945 measured in current dollars:

In addition, it must be noted that since the terrorist attacks on

9-11-2001, the budget of the Department of Defense has not included

either the costs of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq or the costs

associated with Homeland Security. In any case, the Defense Budget in

the 1960s accounted for 50%-60% of all federal spending; so if that is

the baseline, Defense spending started at a much, much higher level than

federal spending on higher education, and so comparing the degree to

which the two amounts have increased as a percentage is almost

inevitably going to be very, very misleading.

Campos’ article also includes these paragraphs: “Some of this

increased spending in education has been driven by a sharp rise in the

percentage of Americans who go to college. While the college-age

population has not increased since the tail end of the baby boom, the

percentage of the population enrolled in college has risen

significantly, especially in the last 20 years. Enrollment in

undergraduate, graduate and professional programs has increased by

almost 50 percent since 1995. As a consequence, while state legislative

appropriations for higher education have risen much faster than

inflation, total state appropriations per student are somewhat lower

than they were at their peak in 1990. (Appropriations per student are

much higher now than they were in the 1960s and 1970s, when tuition was a

small fraction of what it is today.)

“As the baby boomers reached college age, state appropriations to

higher education skyrocketed, increasing more than fourfold in today’s

dollars, from $11.1 billion in 1960 to $48.2 billion in 1975. By 1980,

state funding for higher education had increased a mind-boggling 390

percent in real terms over the previous 20 years. This tsunami of public

money did not reduce tuition: quite the contrary.”

Campos’ choice of 1980 is a very interesting one here because, in

most states, 1980 was actually the high-water mark in terms of the

percentage of the costs at public colleges and universities that were

covered by state subsidies. The Carter-Reagan recession of the late

1970s and early 1980s, the Bush recession of the early 1990s, the Bush

recession of the early 2000s, and the Great Recession of 2008, each

accelerated what were otherwise steady declines in state spending on

higher education as a percentage of the total cost. It is very widely

documented and simply unarguable that the increase in costs being borne

by students has been the inverse in the decline in support being

provided by the states.

Moreover, state support for higher education has been declining even

as the demand for higher education, by percentage of the population—and,

in particular, by percentage of the traditional college-age

population—has been increasing. In the early 1980s, the reductions in

state support may not have been in real revenues but, instead, in the

sizes of the increases that the institutions had requested, but since

the early 1990s and certainly since the 2008 recession, the cuts have

been in real dollars. To cite just a very salient example, Bobby Jindal

has been cutting state support for higher education year in and year out

since he was elected. Because of very ill-conceived state tax cuts,

higher education may have to absorb $300-$400 million of the projected

$1.4 billion budget shortfall that the state is currently facing. If

some miraculous fix is not found, those cuts will have a devastating

impact of public colleges and universities in the state. That situation

simply has nothing to do with how the institutions are spending

available revenues.

Indeed, Campos shifts from citing percentage increases to citing

changes in raw dollar totals when doing so suits his argument—and that

sort of selective and inconsistent number-crunching undermines the

credibility of his analysis: “State appropriations reached a record

inflation-adjusted high of $86.6 billion in 2009. They declined as a

consequence of the Great Recession, but have since risen to $81 billion.

And these totals do not include the enormous expansion of the federal

Pell Grant program, which has grown, in today’s dollars, to $34.3

billion per year from $10.3 billion in 2000.”

But that brings us to what Campos does get right. He rightly

emphasizes that any increases in spending on higher education have not

gone to faculty compensation or even to an increase in full-time

faculty, despite the steady increases in enrollment: “Interestingly,

increased spending has not been going into the pockets of the typical

professor. Salaries of full-time faculty members are, on average, barely

higher than they were in 1970. Moreover, while 45 years ago 78 percent

of college and university professors were full time, today half of

postsecondary faculty members are lower-paid part-time employees,

meaning that the average salaries of the people who do the teaching in

American higher education are actually quite a bit lower than they were

in 1970.”

He then notes the dramatic increase in allocations for administrative

positions, administrative compensation, and administrative support

staff:

“By contrast, a major factor driving increasing costs is the constant

expansion of university administration. According to the Department of

Education data, administrative positions at colleges and universities

grew by 60 percent between 1993 and 2009, which Bloomberg reported was

10 times the rate of growth of tenured faculty positions.

“Even more strikingly, an analysis by a professor at California

Polytechnic University, Pomona, found that, while the total number of

full-time faculty members in the C.S.U. system grew from 11,614 to

12,019 between 1975 and 2008, the total number of administrators grew

from 3,800 to 12,183 — a 221 percent increase.

“The rapid increase in college enrollment can be defended by

intellectually respectable arguments. Even the explosion in

administrative personnel is, at least in theory, defensible. On the

other hand, there are no valid arguments to support the recent trend

toward seven-figure salaries for high-ranking university administrators,

unless one considers evidence-free assertions about “the market” to be

intellectually rigorous.”

Even though he lays out many of the relevant elements, what Campos

doesn’t really get at is that, regardless of who is footing the bill,

the “real cost” of higher education–that is, expenditures per

student–has not risen much since 1970. But what have changed

dramatically are the percentages of the institutional revenues that are

being allocated to administration and to instruction. The rise in the

exploitation of both part-time and full-time contingent faculty is

directly related to the transfer of allocations from tenure-track

faculty lines to administrative budget lines.

At most public universities, less than a quarter of all spending is

now devoted to faculty salaries and benefits and less than half of all

spending is devoted to everything that might be even remotely construed

as instructional support.

Several years ago, in another post, I commented wryly on our

administrations being preoccupied with planning for our institutions’

post-educational futures. I realize now, even more than I did then, that

I may have been laughing into the abyss.

No comments:

Post a Comment