This from the

Bowling Green Daily News:

Kentucky

has come a long way from ranking near the bottom in K-12 education, and

a new report contends it's because of state legislation that helped

usher in key changes more than 20 years ago.

The

report was recently released by the Prichard Committee for Academic

Excellence and the Kentucky Chamber of Commerce. It says that the 1990

passage of the Kentucky Education Reform Act brought a range of changes

to public education in the state. They include helping to end the

problem of nepotism hiring in school districts, creating higher

standards for students, creating the state's first system for testing

those standards and equalizing funding among poor and wealthy school

districts, among other reforms.

Cory

Curl is the associate director of the Prichard Committee, which was

founded in 1983 to help public education in Kentucky move forward.

Back then, Curl said Kentucky

ranked 50th in the in nation for percentage of adults with high school

diplomas and 50th in adult literacy.

"Kentucky

has a really remarkable story to tell about how educational improvement

can happen when citizens and business and policymakers and parents work

together," Curl said. "We felt like this was a story that needed to be

told in a way that everyone can come to that common understanding."

Kentucky Chamber CEO and President Dave Adkisson also praised the report in a press release.

"We

think this report will help Kentuckians – whether they are policy

leaders, employers or interested citizens – gain a better understanding

of the state’s efforts to improve education through the years," he said.

"It provides a historical perspective while emphasizing the need to

continue to push for excellence."

Kentucky

now ranks among the top 10 in the nation for high school graduation

rates. To move forward, Curl said the state needs to do more to expand

education access and create more opportunities for low income and

minority students.

A

state-by-state report released by the Education Week Research Center

earlier this year gives Kentucky an overall grade of C and a rank of 27.

That report also placed fourth and eighth-grade reading and math

proficiency at just above the national average, with Kentucky ranking at

roughly 36 percent compared to 34.8 percent nationally. Kentucky

students participating in school lunch assistance programs are still

behind on proficiency, ranking below the national average of 30.1

percent at 26.3 percent.

Despite

ongoing hurdles, Kentucky has progressed since the passage of KERA. In

1983, economist David Birch described Kentucky as a third world country

with the nation's most uneducated workforce.

Real

change didn't begin until 1985 when 66 of the state's poorer school

districts sued the state arguing that funding was insufficient and

unequal. In 1989, the Kentucky Supreme Court ruled in Rose v. Council

for Better Education that the state's public school system was entirely

unconstitutional.

The fallout forced the General Assembly to not just equalize but recreate public education funding, the report says.

For

Curl, the biggest achievement of KERA was the creation of the Support

Education Excellence in Kentucky program to equalize school funding

across districts. A close second is the first real success at creating a

system to test how well students meet standards, she said.

It allowed the committee to look at which schools had top reading scores, for example.

"It

gave the public access to that kind of information," Curl said. "So it

changed mindsets. It showed what was possible when students have access

to high quality instruction."

When it comes to the state's current challenges, higher education access stands out.

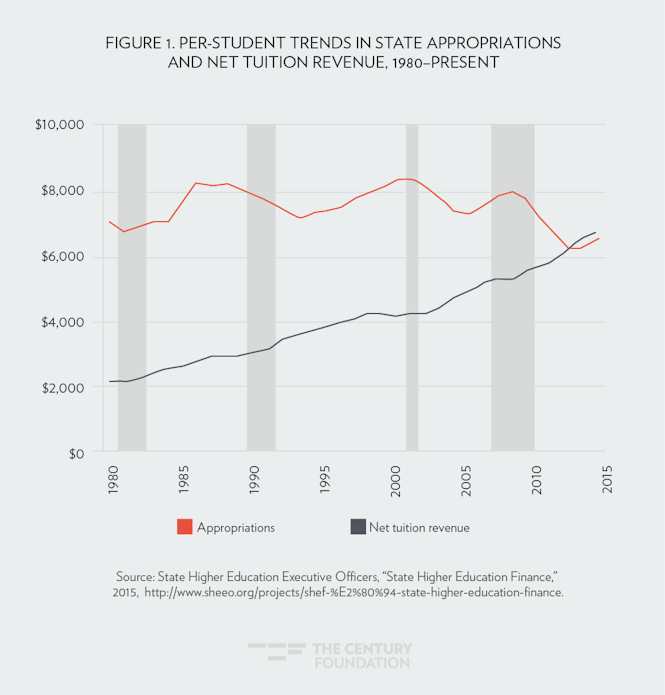

A

breakdown of the total revenue of Kentucky's public post-secondary

institutions by source shows that state general fund dollars as a source

of funding have fallen from 30 percent in 2003 to 14 percent in 2015.

Meanwhile,

money from tuition and fees now is more than a quarter of total

revenue. It made up 17 percent in 2003 and 26 percent in 2015.

The drop in funding is a concern Curl said the committee is watching.

Erin

Klarer, vice president of government relations with the Kentucky Higher

Education Assistance Authority, agrees it's concerning.

"The cost of attendance (to college) has

certainly increased significantly while state appropriations have

decreased," she said.

What's fueling the trend is a change in the way education is viewed by policy makers, she said.

“It

is a philosophical question as to whether the cost of post-secondary

education should be borne by those who consume it or it should be funded

by the government," she said.

Emboldened

by the federal Every Student Succeeds Act that shifts power to states

and local districts, the Kentucky Department of Education is creating a

new system for testing student success in meeting standards.

Sam

Evans is the dean of Western Kentucky University's College of Education

and Behavioral Sciences. He recently visited Frankfort to discuss the

new accountability system with Education Commissioner Stephen Pruitt and

others on a steering committee. Over the next six months, Evans said,

work groups will review public feedback and group it into common themes

to help inform the new system.

At

the meeting, Evans said conversation mostly centered on moving away

from one single metric for school success to a more "dashboard" approach

that shows growth in several areas and discourages competition among

districts.

"If we can move in that direction, that’s gonna be huge," he said.

In

designing the new system, Evans stressed due diligence and said without

it "it’s going to be a recipe for failure down the road."